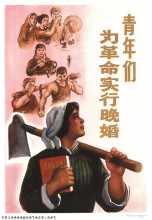

The New Marriage Law that was promulgated on 1 May 1950 gave women legal equality with men. In a sense, the law formed the logical conclusion of the struggle that had started during the May Fourth Movement (1919) to bring to an end the influences of the patriarchy and ageism that existed in the feudal family system. In practice, the law followed an earlier one that had been promulgated during the CCP's stay in the Jiangxi Soviet in the early 1930s and incorporated experiences gained in Yan'an. The implementation of the Marriage Law overlapped the Land Reform movement in many places, particularly in the newly-liberated areas, and caused considerable confusion.

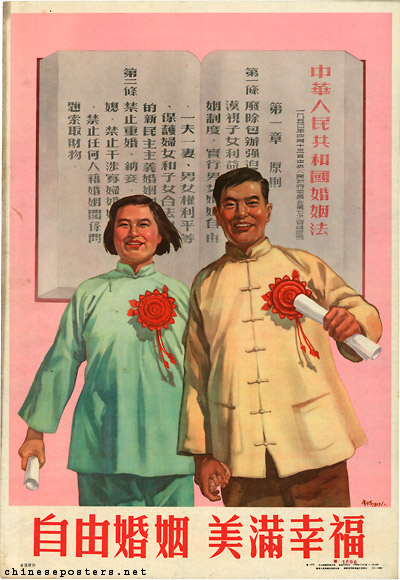

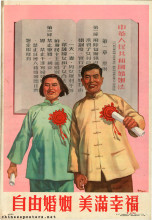

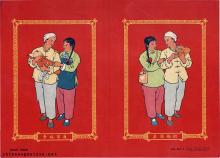

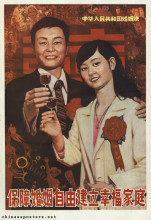

Freedom of marriage, happiness and good luck, 1953

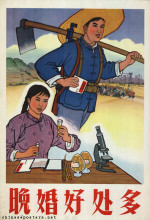

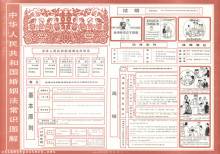

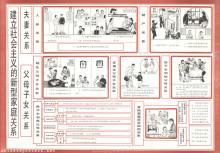

Chapter One, Article One of the law, for example, defined that marriages should be based on the free choice of partners, on monogamy, on equal rights for both sexes, and on the protection of the lawful interests of women and children. Many of the elements of the law had legislative antecedents and were less revolutionary than they seemed. The freedom of choice regarding partners was a continuation of rules set out in earlier Republican marriage regulations, as were the freedom of divorce, the ban on polygamy and taking concubines, and the ban on child marriages. The CCP introduced a number of new elements as well. One of these was that couples were ordered to register their marriages (or divorces) at state institutions.

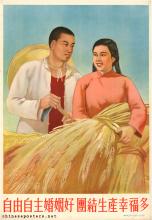

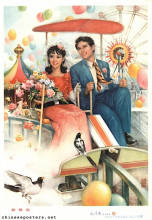

A free and independent marriage is good, there is great happiness in unified production, 1953

Another new element provided by the marriage law was that it defined relations between generations: children, parents and grandparents had to live in harmonious relations and care for each other. Despite these provisions, many elderly in particular were prosecuted as 'landlords' when they resisted the new approach to marriages, which often offended traditional attitudes and sensibilities toward the choice of spouse and cohabitation.

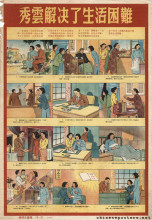

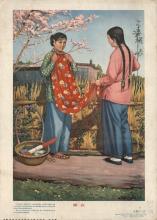

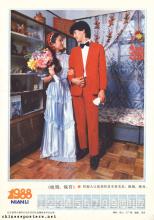

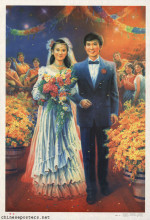

A happy marriage, a happy family, 1955

The law led many to believe that its notion of 'free love', i.e. marriages that were not coerced or arranged, actually meant that people could have sex with whomever one wanted. On the other hand, the introduction of the law also led to large numbers of marriage-dispute cases, divorces, murders and suicides. Until 1955, yearly propaganda campaigns were organized to publicize the law all over the land. By then, more than 90% of all marriages had been officially registered and these were considered to have been concluded in free will.

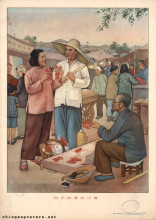

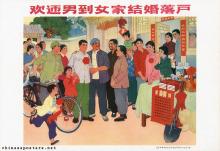

In marriage, keep an eye on your own interests, and return radiant after registration, 1953

Neil J. Diamant, "Re-examining the Impact of the 1950 Marriage Law: State Improvisation, Local Initiative and Rural Family Change", The China Quarterly No. 161 (March 2000), pp. 171-198

Neil J. Diamant, "Making Love ‘Legible’ in China: Politics and Society during the Enforcement of Civil Marriage Registration, 1950-66", Politics & Society, vol. 29 no. 3 (September 2001), pp. 447-480

E. Stuart Kirby (ed.), Contemporary China 1955 (London: Oxford University Press 1956)