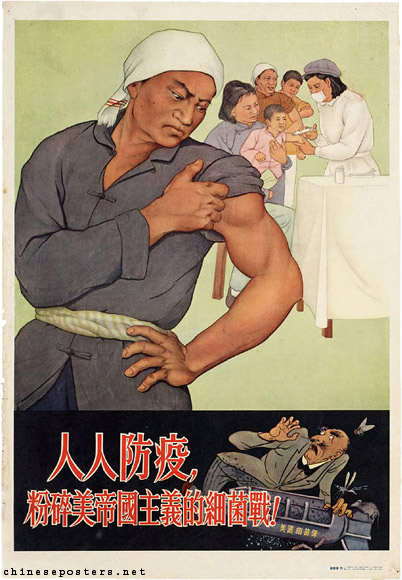

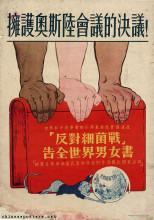

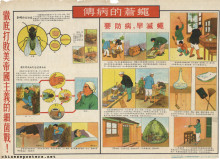

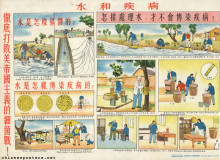

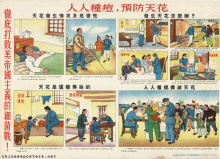

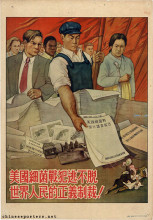

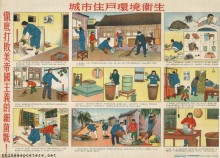

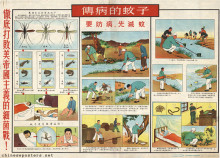

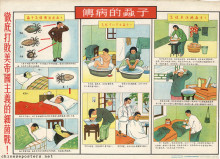

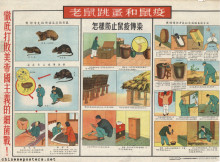

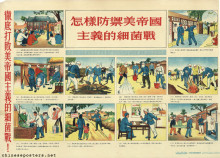

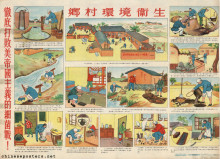

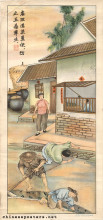

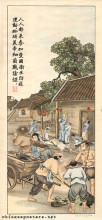

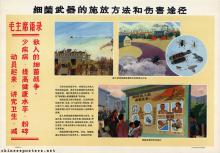

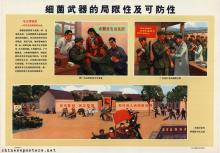

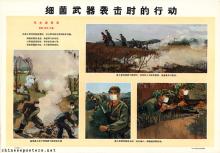

The Patriotic Health Campaign of 1952 started after the appearance of "poisonous insects" in the winter of 1951-1952. American germ-warfare in North Korea had already been reported earlier, but in early 1952, the People’s Daily (Renmin ribao) explicitly linked these reports with the occurrence of domestic epidemics. In March 1952, eyewitness accounts confirmed the spraying of germs by Americans in Manchuria and Qingdao. This followed hot on the heels of the start of the ceasefire negotiations at Panmunjom that were to end the Korean War. From then on, official newspapers carried reports that offered more and more details about germ-warfare having moved into China itself. Broken germ bombs were found, as were scattered pamphlets with flies and fleas on them; the shells were marked with phrases such as "U.S.TIME" and "BMBOBLEAFLET", similar to those dropped in Korea. The reports did not confirm a connection between the local epidemics that took place and germ-warfare, but by deliberately blurring the differences between the two, the government wanted to encourage public hygiene and health work. Thus, the elimination of rats, fleas and flies, garbage removal, drinking clean water, not eating raw or cold food and preventive injections should be made everybody’s responsibility.

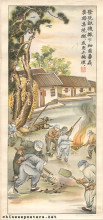

When the germ attacks were confirmed, the Chinese leadership established a central committee for epidemic prevention and launched programs for anti-epidemic injections. Apart from a massive program of injections, all germ-carrying animals were destroyed, special hospitals for inflicted patients were designated and measures taken to quarantaine inflicted areas. At the same time, the anti-epidemy policy took on a different character, one of a nationwide mobilization for social change. The two key components were: to get people in non-disease inflicted areas as deeply involved in the disease prevention movement as people in the inflicted areas so as to establish a routine state penetration in people’s daily lives; and to make people become accustomed to accepting state influence through a massive anti-epidemic campaign. By 1953, a complete institution of disease prevention had been established.

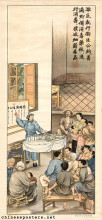

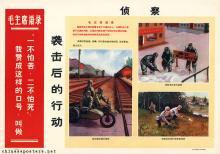

To do a good job in epidemic prevention and hygiene work is concrete patriotic behavior ..., 1952

Abigail Holst, Chinese Propaganda Posters in Mao’s Patriotic Health Movements: From Four Pests to SARS (BA Thesis, Emory University, Atlanta, 2016)

Andrew Kuech, "Cultivating, Cleansing, and Performing the American Germ Invasion: The Anatomy of a Chinese Korean War Propaganda Campaign", Modern China (2019), 1-30

Milton Leitenberg, "China’s False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United States during the Korean War", CWIHP Working Paper 78 (2016)

Thomas Powell, "Biological Warfare in the Korean War: Allegations and Cover-up", Socialism and Democracy 31:1 (2017), 23-42

Ruth Rogaski, "Nature, Annihilation, and Modernity: China’s Korean War Germ-Warfare Experience Reconsidered", Journal of Asian Studies 61:2 (2002), 381-415

Nianqun Yang, "Disease Prevention, Social Mobilization and Spatial Politics: The Anti Germ-Warfare Incident of 1952 and the ‘Patriotic Health Campaign’", The Chinese Historical Review 11:2 ( 2004), 155-182