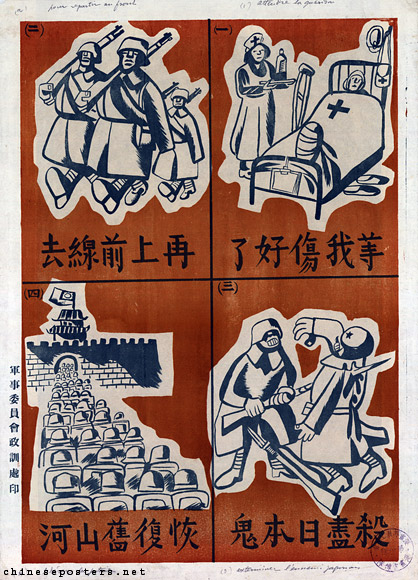

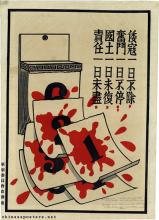

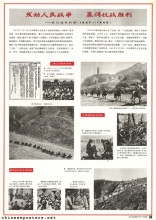

Joining the army to serve the country is the citizens' duty, ca. 1938

Attracted by the cheap labor force and vast resources, Japan invaded China in 1937. The conflict started with the Marco Polo Bridge Incident near Beijing, an exchange of shots engineered by the Japanese in 1937 that served as a pretext for Tokyo to launch a large-scale invasion. Later that year, on 13 December, Japanese troops entered the former Nationalist capital of Nanjing and unleashed a reign of terror, executing POWs and civilians, raping women by the thousands while burning and looting the city.

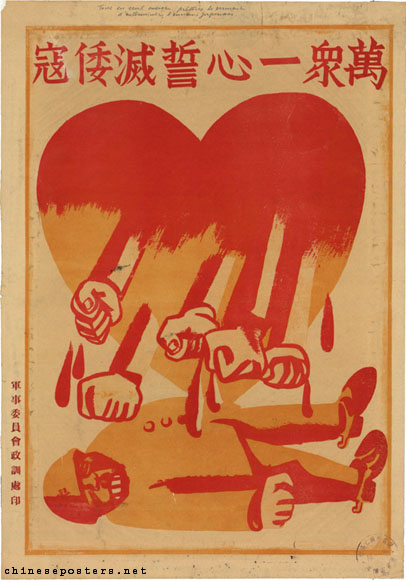

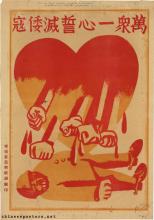

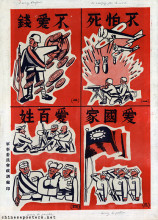

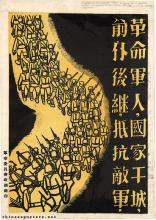

Millions of people all of one mind swear to exterminate the Japanese pirates, ca. 1938

China had to become part of a Japanese designed ‘East Asian Economic Co-Prosperity Sphere’. To that end, Japan already much earlier had started a policy of encroachment. In September 1931, the Guandong Army had launched the Manchurian Incident and began the occupation of Northeast China; the following year it installed Puyi, the last and former emperor of the Qing dynasty, as chief executive (he was enthroned in 1934), and a state was formed; all real power in national defense and government were held by the Guandong Army, and Manzhouguo (Manchukuo, 満州国) thus became the military and economic base for the Japanese invasion of the Asian mainland.

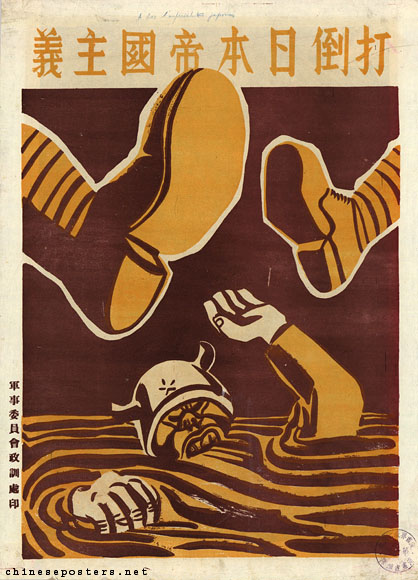

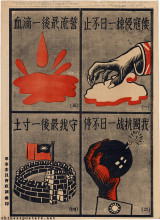

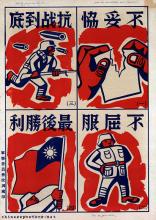

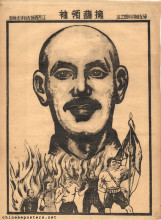

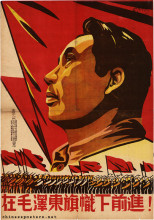

Defeat Japanese imperialism, ca. 1938

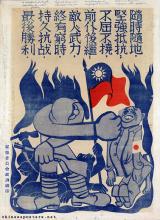

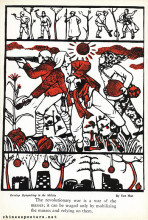

At the time the war started, the bulk of China was controlled by the Nationalist Party (Guomindang, 国民党, old transcription: Kuomintang), which initially was especially strong in the urban areas along the Eastern seaboard but moved inland and established its wartime capital in Chongqing. The Communists had entrenched themselves in "liberated areas" in the countryside, including Yan’an in the Northwest. The military conflict became known as the "Second Sino-Japanese War" (the First Sino-Japanese War was from 1894 to 1895), or the "War of Resistance Against Japan" (抗日战争). It marked the beginning of the Second World War in the Pacific, ending only with the surrender of Japan in 1945. The war cost at least 20 millions of lives, although the exact number of casualties is still heavily debated. It was a cruel war, including targeted bombing of civilians, murder, torture, human experiments and rape, and the use of chemical and bacteriological weapons.

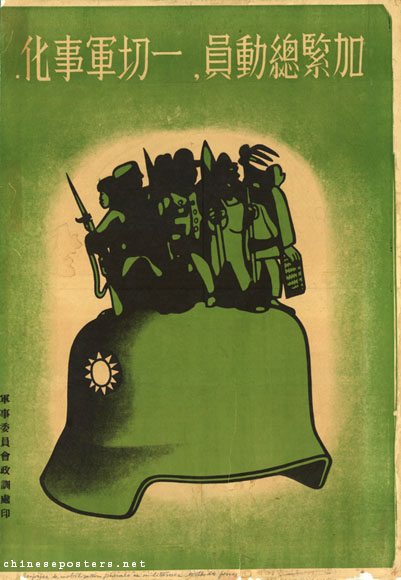

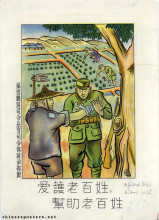

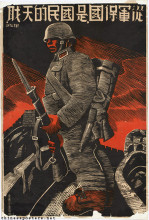

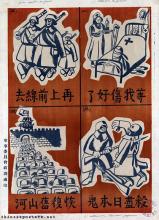

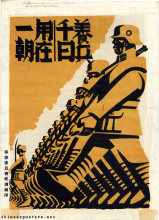

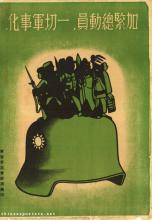

Step up general mobilization, for total militarization, ca. 1938

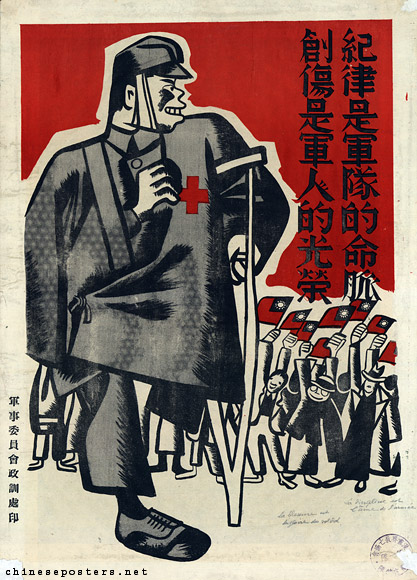

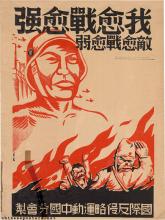

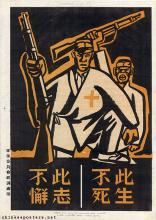

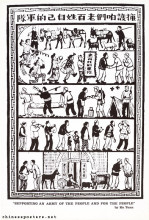

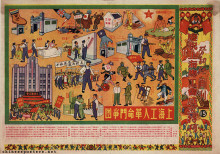

Both the Japanese and the Chinese used posters to try and influence the Chinese population. The Japanese tried to justify their military presence, to make it clear that any resistance was useless and to warn the population against co-operating with either the Nationalists or the Communists. Both the Communists and Nationalists tried to mobilize the population to resist the common enemy, Japan. The posters shown here, published by the Nationalist government, are extremely rare. Posters produced in the liberated areas under Communist control are possibly even rarer; in many cases, only a single copy of such posters ever existed.

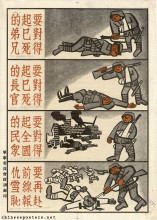

Everbody hates the enemy, set up defenses step by step ..., ca. 1938

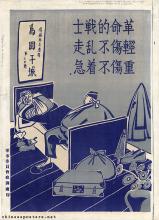

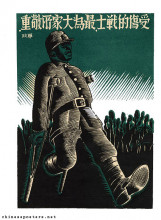

Discipline is the lifeblood of the army, wounds are the glory of the soldier, ca. 1938

Quite a few of the Nationalist posters feature wounded soldiers. They are praised for their sacrifice, encouraged to get well soon and given time to heal - in order to go back to the front.

Wait till my wounds have healed, then I’ll go back to the front, ca. 1938

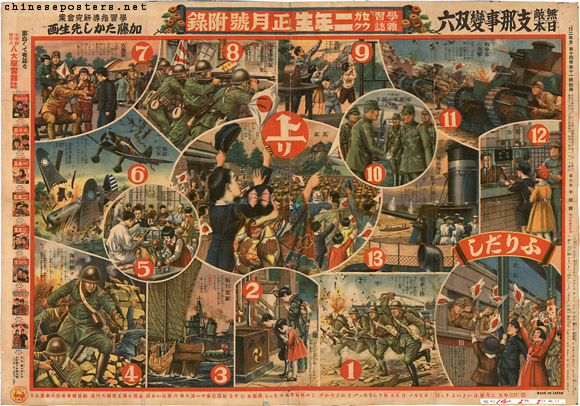

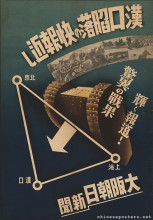

The posters below are pro-Japanese. The first and second, produced in Japan or in the Japan-dominated puppet state of Manzhouguo, take aim at the Communist Party. The third, designed and produced in Japan, praises the exploits of the Japanese army and the support of the home front.

Look! Look! The cruel injustice of the Communist Party, ca. 1938

Invincible Japan - China Incident board game, 1939

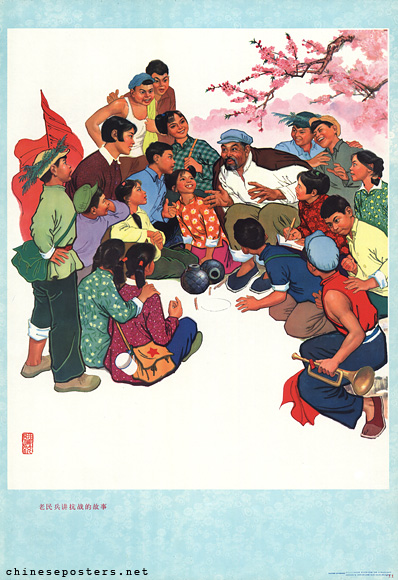

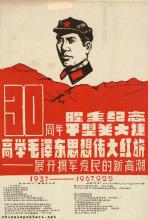

Heroes and episodes from the "War of Resistance" feature prominently in the propaganda of the People’s Republic.

The old militia member tells stories from the War of Resistance, 1973

Parks M. Coble, "China's 'New Remembering' of the Anti-Japanese War of Resistance, 1937–1945", The China Quarterly 190 (2007), 394-410

Parks M. Coble, China's War Reporters -- The Legacy of Resistance Against Japan (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015)

Isabel Brown Crook & Christina Kelley Gilmartin, with Yu Xiji, compiled and edited by Gail Hershatter & Emily Honig, Prosperity’s Predicament -- Identity, Reform, and Resistance in Rural Wartime China (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2013)

Kirk A. Denton, "Exhibiting the Past: China's Nanjing Massacre Memorial Museum," The Asia-Pacific Journal 12:20 (2014)

Joseph Esherick, "Review Essay -- Recent Studies of Wartime China", Journal of Chinese History 1 (2017), 183–191

Rana Mitter, China's War With Japan 1937-1945 (London: Allen Lane, 2013)

Mo Tian, "The Legacy of the Second Sino-Japanese War in the People’s Republic of China: Mapping the Official Discourses of Memory", The Asia Pacific Journal 20:11:4 (2022)

Margherita Zanasi, "Globalizing Hanjian: The Suzhou Trials and the Post–World War II Discourse on Collaboration", American Historial Review (2008), 731-751

Qiang Zhang & Robert Weatherley, "Owning up to the past: the KMT's role in the war against Japan and the impact on CCP legitimacy", The Pacific- Review 26:3 (2013), 221-242