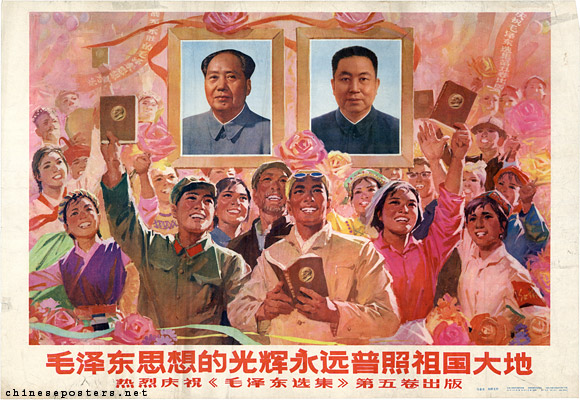

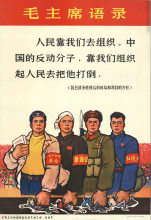

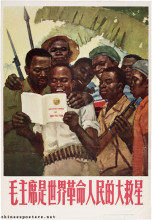

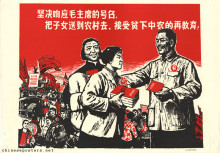

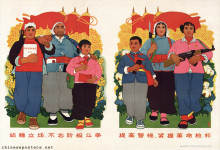

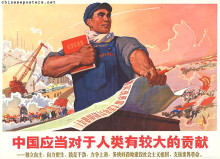

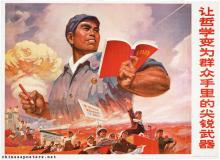

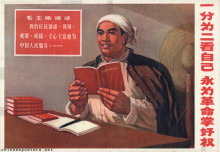

Chairman Mao’s writings sparkle like gold, 1977

Only two days after Hua Guofeng had succeeded in wresting power from the Gang of Four in 1976, a month after the death of Mao Zedong, the Central Committee of the CCP decided that work was to start in preparation of the publication of new, additional volumes of the Selected Works of Mao Zedong (Mao Zedong xuanji - 毛泽东选集). Although Mao already had ordered Zhou Enlai and Kang Sheng in the late 1960s to prepare the publishing of the fifth and even sixth volumes of selections from his Thought, this activity had been brought to a stand-still as a result of the fierce and destructive factional struggles in the Cultural Revolution. Nonetheless, the work as published basically followed the structure laid out in the late 1960s.

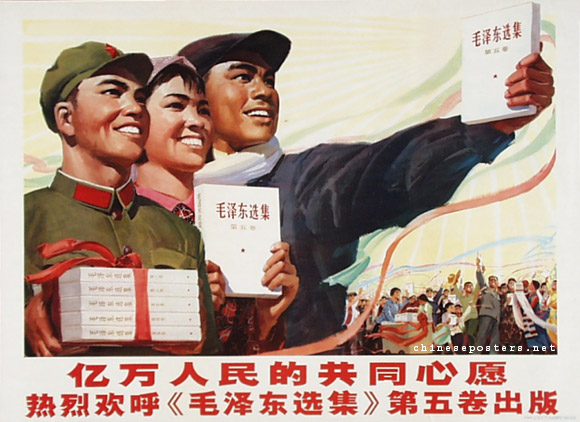

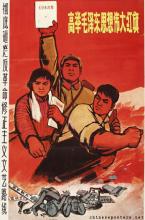

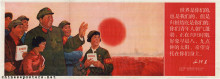

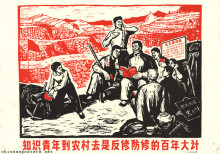

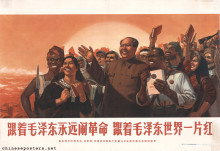

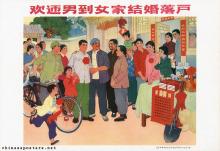

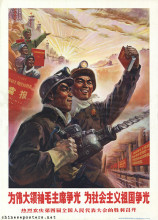

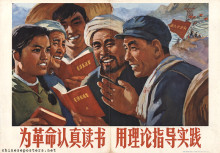

What I longed for has arrived, 1978

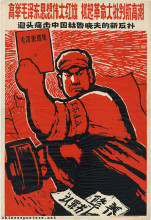

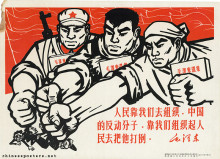

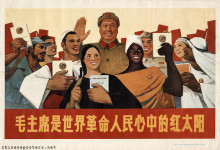

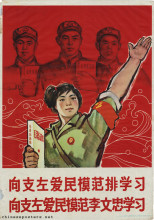

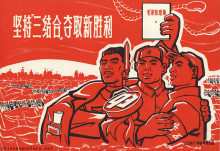

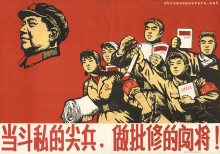

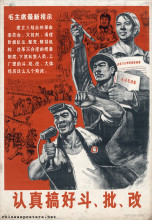

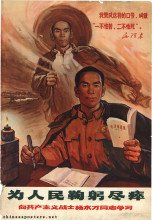

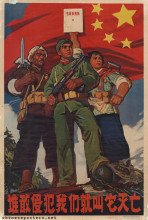

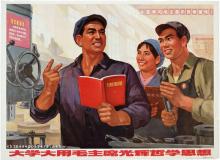

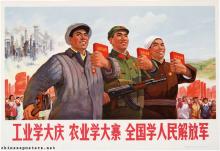

The Volume V that was published under Hua’s direct leadership only six months later, in April 1977, brought to an end the irregular publication activities that resulted from the ransacking of ministeries and archives during the Cultural Revolution. The volume was remarkable for a number of reasons. First of all, it made it clear that the new government had absolutely no desire to start a de-Maofication. It showed that Mao’s writings would continue to serve as useful ideological precepts and that Mao as the founding father of the Chinese Revolution could not be assailed. To bring this continued veneration of Mao about, his more pragmatic decisions and writings were highlighted, whereas his radical ideas that had proven disastrous (Great Leap Forward, Cultural Revolution) were downplayed as much as possible. Moreover, Volume V established Hua as the officially legitimated interpreter of the Mao legacy. As such, it played a major role in Hua’s attempts to style himself as a new leader à la Mao, attempts that included Hua’s ill-fated ‘two-whatevers’-policy and changes in his appearance and hairstyle that were intended to make him look more like his predecessor. Volume V therefore became a recurring theme in the propaganda campaign centering on Hua.

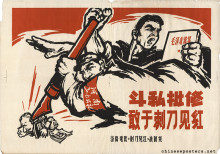

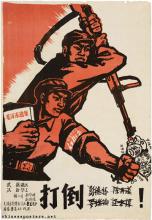

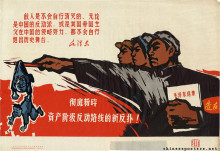

The 500-page Volume V, heralded as China’s major literary event of 1977, brought the date of Mao’s writings closer to the present: it contained a selection of the essays written in the period 1949-1957, i.e., from the founding of the PRC to the end of the Hundred Flowers Movement. Mao’s 1956 speech ’On the Ten Major Relationships’  formed the centerpiece of the book, serving as a blueprint for the pragmatic conception the new leadership had of social development. The new writings rehabilitated many of the functionaries who had fallen victim of the Cultural Revolution and bestowed a tribute on Zhou Enlai that had been withheld by the Gang. The preface, moreover, singled out the radicals around Jiang Qing for persecution by presenting them as ‘ultra-leftists’, who in reality were ‘right-wing’ revisionists.

formed the centerpiece of the book, serving as a blueprint for the pragmatic conception the new leadership had of social development. The new writings rehabilitated many of the functionaries who had fallen victim of the Cultural Revolution and bestowed a tribute on Zhou Enlai that had been withheld by the Gang. The preface, moreover, singled out the radicals around Jiang Qing for persecution by presenting them as ‘ultra-leftists’, who in reality were ‘right-wing’ revisionists.

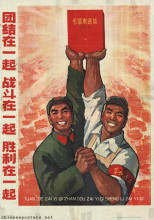

The publication was a resounding success. According to incomplete statistics, by the end of April 1977, more than 28 million copies had been distributed. A study campaign was started, accompanied by study articles written by leading cadres, including Hua, that dominated the Chinese press for months.

Volume V seems to be the last volume of the Selected Works that saw the light for a long time to come. Once Deng Xiaoping returned to his position of power in 1977, he started to subvert Hua’s position and the latter’s pretension of being a new leader in the vein of Mao. Once the Third Plenum of the Eleventh Central Committee decided in December 1978 that all the Party’s efforts should be focussed on building the economy, while downplaying political movements and purges in the same breath, it became clear that the publication of subsequent volumes would take considerable time. Politics obviously were no longer in command. The editorial committee for Volume VI, which would span the period of the Great Leap Forward to the early 1960s, was disbanded.

This was partly the result of the fact that the political climate had changed considerably. With such prominent victims of Mao’s as Peng Dehuai and Liu Shaoqi rehabilitated, it was unavoidable that the political maneuverings of Mao and his followers would have to come in for criticism. In fact, the new way of looking at things political that was introduced by Deng could lead to a situation where further publication of Mao’s writings would become more of a catalogue of his scheming, errors and mistakes. This could jeopardize the status of Mao Zedong Thought as one of the pillars of the PRC.

Resolution on CPC History (1949-81) (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1981)

Ding Wang, Chairman Hua - Leader of the Chinese Communists (London: C. Hurst & Company, 1980)

John Gardner, Chinese Politics and the Succession to Mao (London: The Macmillan Press Ltd, 1982)

Kwok-sing Li (editor) & Mary Lok (translator), A Glossary of Political Terms of the People's Republic of China (Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 1995)

Helmut Martin, Cult & Canon - The Origins and Development of State Maoism (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe Inc., 1982)

Rudolf G. Wagner, "Reading the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall in Peking: The Tribulations of the Implied Pilgrim", Susan Naquin & Chün-fang Yü (eds), Pilgrims and Sacred Sites in China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992)