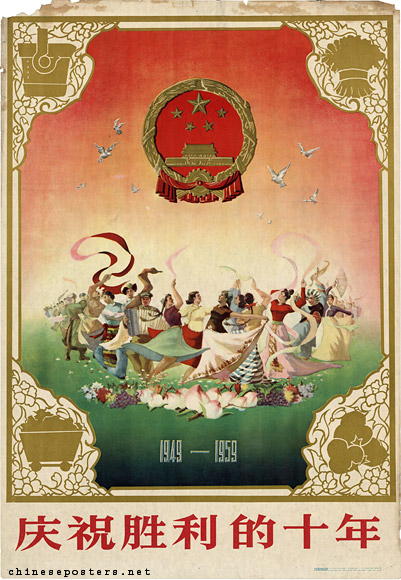

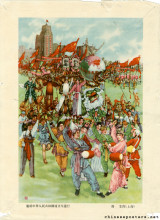

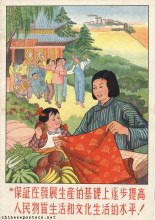

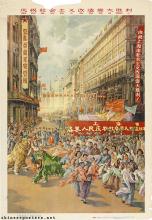

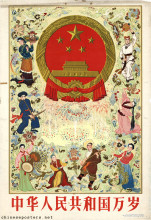

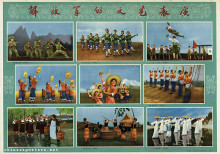

Celebrate ten years of victory, 1959

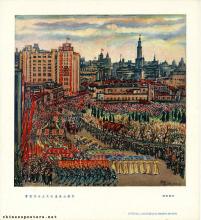

Chinese propaganda is not, nor has not always been exclusively concerned with mobilizing the people into huge mass movements. On the contrary, over the decades many posters have appeared that illustrate how happy the Chinese could be. In 1959, for example, when the People’s Republic celebrated its tenth birthday, a celebratory poster was issued (above).

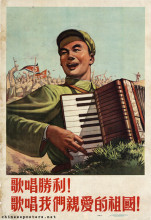

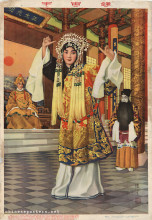

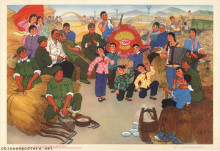

A thousand year old zheng obtains new life, 1975

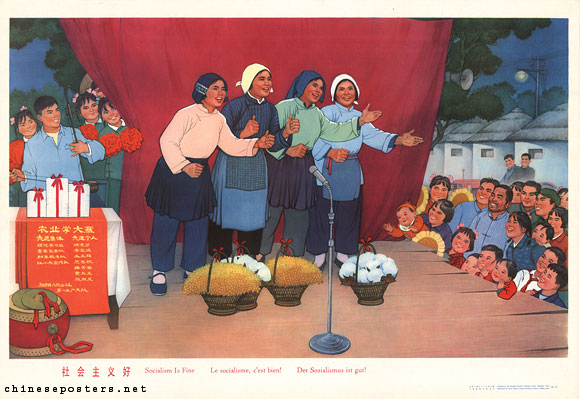

In the early 1960s and during the Cultural Revolution, there were few opportunities to really rejoice. The revolutionary operas (yangbanxi), sponsored by Jiang Qing, were among the few moments where people could enjoy music and dance. Many scenes from these operas made their way to posters. Of course, many other posters were published which showed the people praising the merits of socialism.

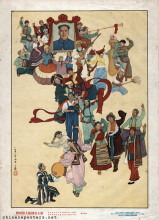

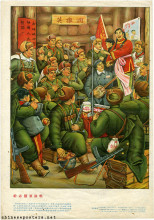

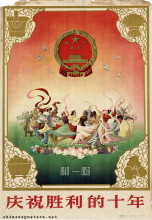

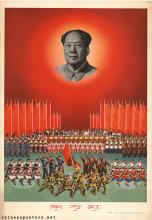

When the Gang of Four was arrested in October 1976, and the Cultural Revolution was officially called to an end, the people did go out in the streets to celebrate. Not necessarily because they were pleased with Hua Guofeng’s rise to power, as below, but because they were convinced that things would now improve.

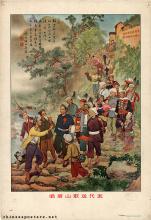

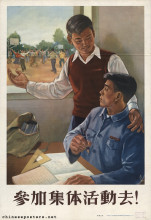

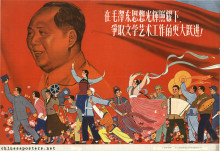

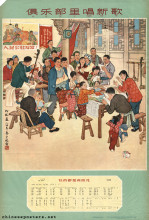

Before the situation did improve, with Deng Xiaoping taking over from Hua in 1978, the Chinese still had to endure some leftover movements from the past. One of these was the official campaign to go out and celebrate the publication of the fifth volume of Mao’s Selected Works, as the poster below illustrates.

Chairman Mao’s writings sparkle like gold, 1977

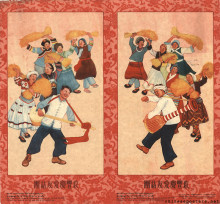

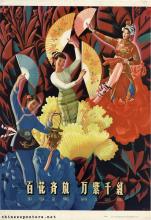

Once Deng embarked on his policy of modernization and reform of the economy, things truly did change. New attention to science and technology, culture and the arts succeeded in revitalizing Chinese society. The famous Peacock Dance, illustrated below on a 1980 calendar, was quite the official rage in the early 1980s, showing a boundless faith in progress.

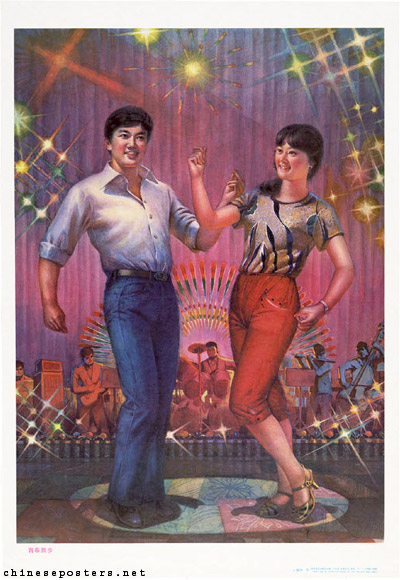

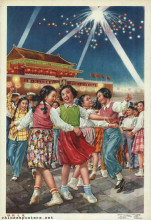

As a result of the reforms, Chinese society did truly change. People engaged in activities that had been unthinkable only a few years earlier. One of the crazes that swept China in the mid-1980s was disco (disike) dancing and music. I have never understood whether the 1986 poster ‘Youthful dancesteps’ was intended to show the people that henceforth, they were allowed to dance, or to signal to local functionaries that dancing from now on was accepted.

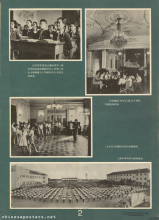

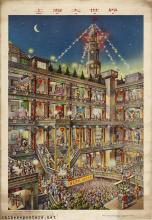

Towards the end of the 1980s, many people considered disco already old-fashioned. Inspired by Japanese business people, and following the custom already fully developed in Hong Kong and Taiwan, karaoke became the favored pastime for many. The popularity of this type of sing-a-long only exploded in the following years. A visit to a karaoke bar, with or without K-ladies, is the way to spend an evening with friends or business acquaintances.

The Party adroitly put this new technology to its own uses. The poster ‘Party oh party, beloved party’, part of a set to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the founding of the CCP, illustrates that people have the Party’s blessing to engage in singalongs. That is to say, they should preferably sing along with tunes that have been approved by the Party. Even in the 00s, many songs from earlier periods of political upheaval can be found in the karaoke-computers. Many a karaoke machine carries tunes praising Chairman Mao. Another all-time favorite is the "anthem" of the Cultural Revolution, Dongfang hong [The East is Red 东方红].

Adam Cathcart, "Japanese Devils and American Wolves: Chinese Communist Songs from the War of Liberation and the Korean War", Popular Music and Society 33:2 (2010), 203-218

Ellen V. P. Gerdes, "Contemporary Yangge: The Moving History of a Chinese Folk Dance Form", Asian Theatre Journal 25:1 (2008), 138-147

Alan L. Kagan, "Music and the Hundred Flowers Movement", The Musical Quarterly 49:4 (1963), 417-430

Ming-yen Lee, "The Politics of the Modern Chinese Orchestra: Making Music in Mao’s China, 1949-1976", Modern China Studies 25:1 (2018), 101-125

Emily Wilcox, "Dancers Doing Fieldwork: Socialist Aesthetics and Bodily Experience in the People's Republic of China", Journal for the Anthropological Study of Human Movement 17:2 (2010/2012), 1-11

Emily Wilcox, "Performing Bandung: China’s dance diplomacy with India, Indonesia, and Burma, 1953–1962", Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 18:4 (2017), 518-539

Emily Wilcox, "The Postcolonial Blind Spot: Chinese Dance in the Era of Third Worldism, 1949–1965", positions 26:4 (2018), 781-815

Emily Wilcox, Revolutionary Bodies: Chinese Dance and the Socialist Legacy (Oakland: University of California Press, 2019)

Emily Wilcox, "Moonwalking in Beijing: Michael Jackson, piliwu, and the origins of Chinese hip-hop", Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 23:2 (2022), 302–321 https://doi.org/10.1080/14649373.2022.2064610