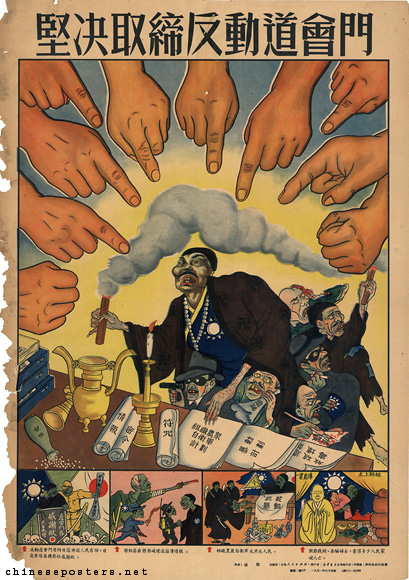

Resolutely ban reactionary secret societies, 1951

Because they were highly flexible and because of the internal chaotic situation prevailing in China, many traditional secret societies had been able to create a place for themselves at various social levels as welfare associations, criminal networks or as spiritual havens. All this was possible by constantly shifting their alliances with the Nationalist Party, the Japanese invaders and even the Communist Party. By October 1949, more than 300 different secret societies existed, with more than 13 million adherents, considerably more numerous than the CCP itself. Moreover, many prominent Partymembers, including He Long and Zhu De, themselves had joined secret societies such as the Gelaohui (哥老會, Society of Elder Brothers) in the 1920s and 1930s. Zhu saw the organisational structure of the societies as an example that should be followed by the Party. And Mao had called upon the Elder Brothers to join the United Front against the Japanese.

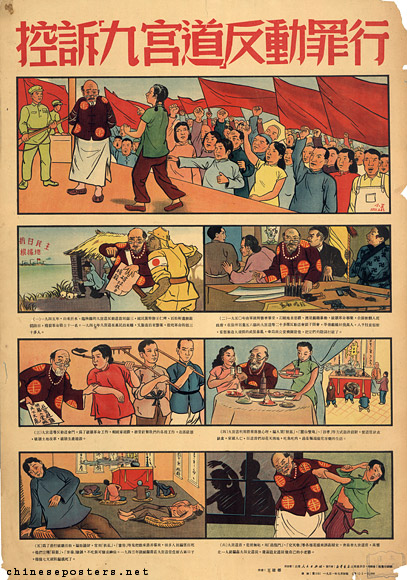

Denounce the reactionary crimes of the ‘Jiu Gong Sect’, 1951

The CCP considered the spiritual-mythical movements such as the Yiguandao (一貫道, Way of Pervading Unity), Jiugongdao (九 宫 道, Nine Temples Way) and Xiantiandao (先天道, Way of Former Heaven), all deeply rooted in tradition and with many adherents among the population, as potential troublemakers that could make use of dissatisfaction and insecurity to try and discredit the new regime and foment rebellion. The new government therefore waged a bitter nationwide struggle, the "Withdraw from the Sects movement" (1951-1953, 退道运动, tuidao yundong) to "eradicate" them. This was because the CCP saw them as a serious threat. First, the secret societies were considered a political and counterrevolutionary threat because of their ties with the Nationalists and - especially during the Korean War - with imperialist, American interests. Secondly, the secret societies almost completely controlled the transport sector in large (harbor) cities, considered a key economic sector.

By the end of the 1950s, the economic and social base of the secret societies had been destroyed. Not necessarily, however, the organisational and ideological principles that were able to continue to exist. In many respects, the emergence of the Falun Gong in the 1990s is considered to be proof of this.

Chang-tai Hung, "The Anti-Unity Sect Campaign and Mass Mobilization in the Early People’s Republic of China", The China Quarterly (2010), pp. 400-420

Steve A. Smith, "Local Cadres Confront the Supernatural: The Politics of Holy Water (Shenshui) in the PRC, 1949-1966", The China Quarterly (2006), pp. 999-1022

Steve A. Smith, "Talking Toads and Chinless Ghosts: The Politics of ‘Superstitious’ Rumors in the People’s Republic of China, 1961-1965", American Historical Review, April 2006, pp. 404-427