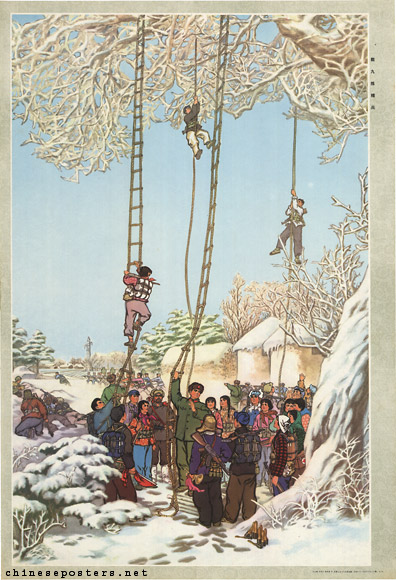

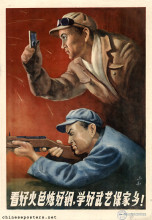

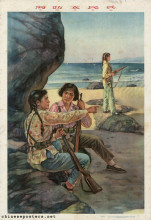

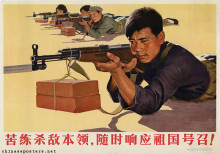

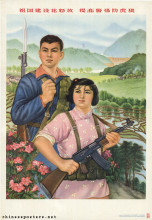

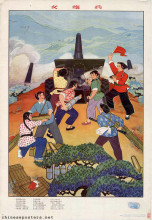

Training crack troops in the coldest time of the year, 1975

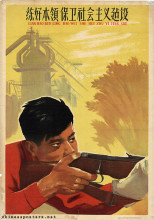

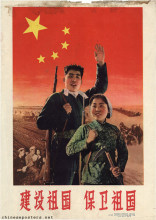

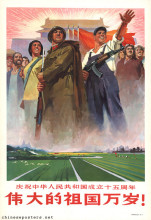

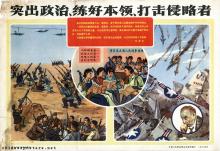

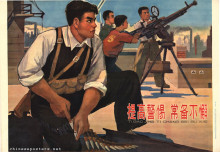

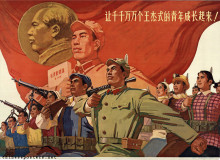

In the late 1950s, the strategy of ‘people’s war’ was revived by Mao, who insisted at the time that men rather than weapons decide wars. Mao’s strategy, strongly supported by Lin Biao, was in opposition of the desire for further professionalization as proposed by various other military men, including Peng Dehuai. The goal of this "everyone-a-soldier"-movement was to maintain control over a vast territory with only thin resources, to protect the national borders, and if necessary, to retreat to the interior to fight a protracted war. In case of attack, space was to be traded for time.

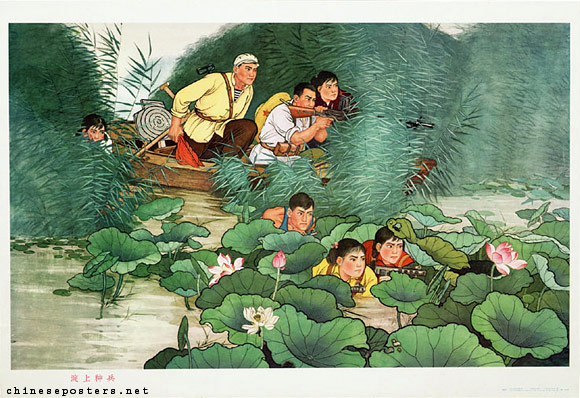

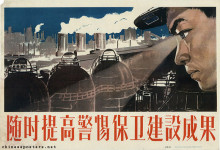

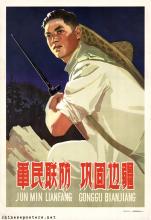

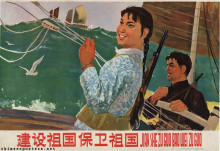

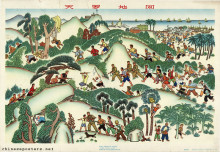

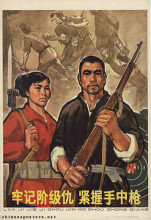

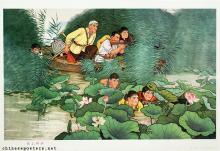

To do this, it was necessary to "lure the enemy deep" and to mobilize popular resistance. As a consequence, the principle of guerrilla warfare against potential invaders was revived, leading to the interpenetration of military and civilian life. Soldiers lived among civilians as "fish in the water", and trained them in waging resistance.

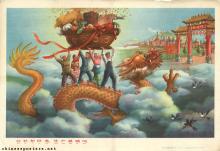

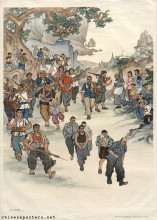

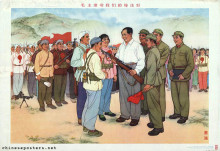

Miraculous soldiers on Baiyangdian Lake, 1966

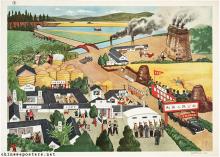

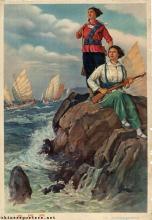

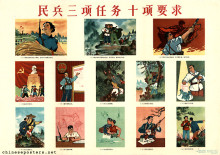

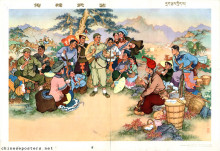

In the 1960s, the Chinese peasantry was organized through the commune system into a vast people’s militia. In all, about a quarter of the population was involved. The militia was given simple training, often with wooden rifles, by militia departments that were staffed by PLA officers. An important part of the training process was ideological work: learning from the various model soldiers that were held up for emulation, such as Lei Feng, Wang Jie, Dong Cunrui, Ouyang Hai and many others. By the same token, many of these model soldiers had attained their martyr status as a result of accidents with life ammunition while training the militias.

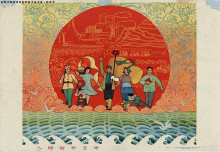

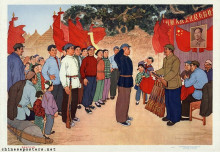

Organize contingents of the people’s militia on a big scale, ca 1969

For all intents and purposes, the militia was trained to resist foreign invasion. In reality, they were more often used to maintain internal security, in particular during such chaotic periods as the Cultural Revolution.

Flemming Christiansen & Shirin Rai, Chinese Politics and Society - An Introduction (London: Prentice Hall 1996)

Ellis Joffe, Party and Army - Professionalism and Political Control in the Chinese Officer Corps, 1949-1964 (Cambridge: Harvard East Asian Monograph 19, 1967)

Andrew J. Nathan & Robert S. Ross, The Great Wall and the Empty Fortress - China’s Search for Security (New York: W.W. Norton & Company 1997)