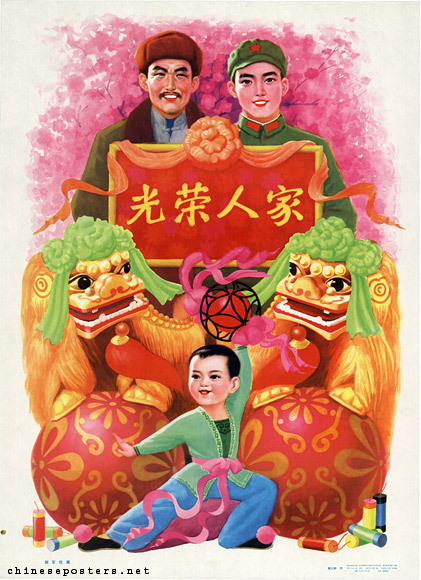

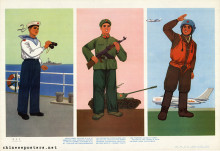

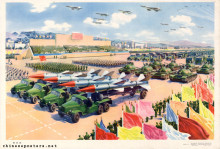

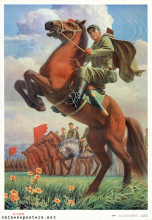

People’s Liberation Army, 1980

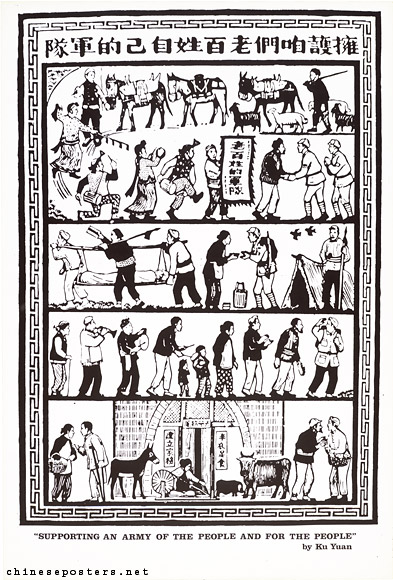

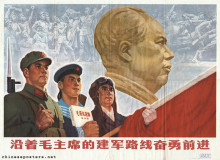

The predecessor of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA, 解放军, Jiefangjun), the Red Army, came into being with the Nanchang Uprising on 1 August 1927. On the basis of Mao Zedong’s theory of "people’s war", this revolutionary army was to have both a political and social role. These roles consisted of doing propaganda among the masses, organizing the masses, arming the masses, helping them to establish revolutionary political power and setting up Party organizations. While doing this, the Party at all times was to maintain control over the army.

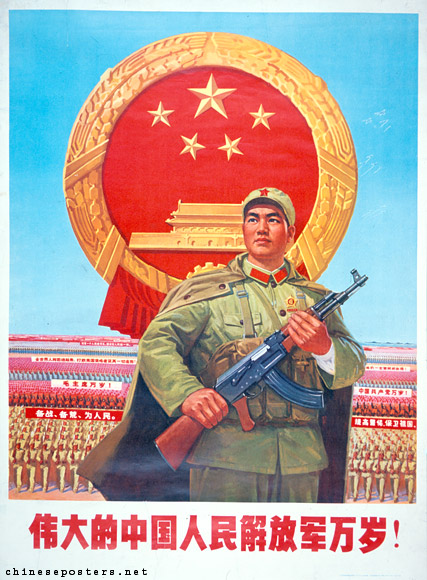

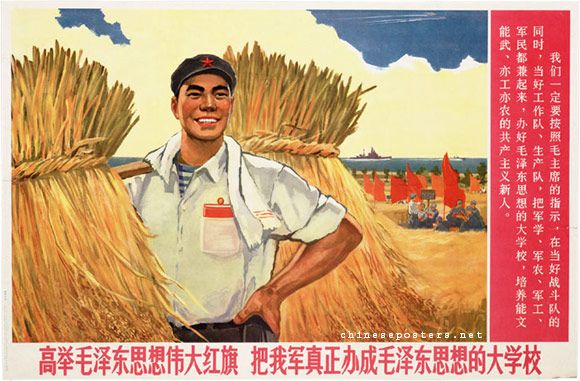

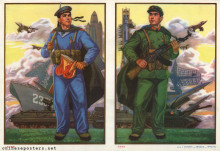

The fact that most Chinese political leaders (Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, Zhu De, Ye Jianying, Lin Biao, and many others) had military careers while at the same time serving in the civilian power structure reflects this dual role of the PLA. The participation of the political elite in military affairs also meant that there was little emphasis on formal training of officers. In the PLA, being "red" was always considered better than being "expert". The political character of the PLA also contributed to the formation of a mystique of the army as a disciplined, politically conscious force that was closely engaged with the task of rebuilding the nation.

Supporting an army of the people and for the people, 1944 (reprint)

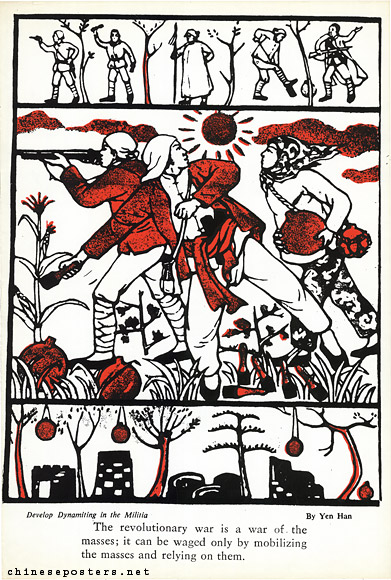

Develop dynamiting in the militia, 1944 (reprint)

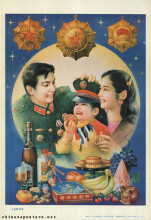

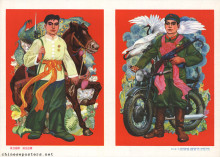

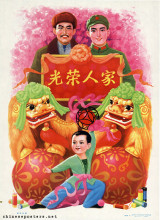

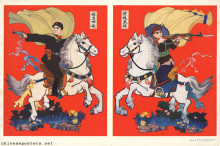

Traditionally, the military had a very low social status in China, aside from a folklore built around romantic soldiers and military heroes of virtue. "Good iron is not made into nails, a good man does not become a soldier", as the popular saying goes. This image changed dramatically during the revolutionary war period; joining the PLA became an aspiration for many young people who felt repressed, in particular for those of worker or peasant background, and women.

Aside from patriotic motives, joining the PLA almost automatically led to acceptance by the Party, and this in turn opened various career prospects. The army enabled young people to acquire skills that were useful in civilian life; demobilized soldiers were honored in their villages and, very importantly, had built up good relations that gave them easier access to the local bureaucracy. Many became cadres themselves, thereby providing status for their families. Others played a major role in national politics, in particular after 1969, when the PLA was called in to restore order after the Cultural Revolution had resulted in total chaos.

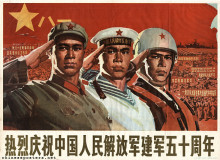

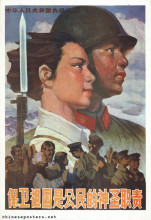

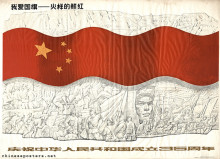

Long live the great Chinese People’s Liberation Army!, 1972

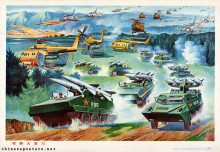

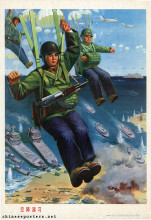

As a fighting force, the PLA has often been able to accomplish astonishing military feats in the face of adversity. Despite often inadquate armaments, the Army succeeded in defeating superior Nationalist forces during the civil war of 1946-1949, paving the way for the founding of the PRC. Although undereducated and underbudgeted, the PLA applied guerrilla tactics, emphasizing flexibility and a close integration with the people. Constant ideological training prepared the soldiers for hardship and sacrifice for the revolutionary cause.

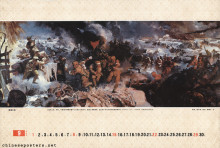

The destruction of the Chiang Kai-shek dynasty, 1978

After the founding of the PRC, the PLA started to play a role in China’s foreign policy by actively engaging in a number of conflicts. The Army fought the American troops in Korea in 1950-1953 and against India in 1962 (unresolved until the present day); it clashed with former ally the Soviet Union along the shared Northeastern border in 1969; battled with South-Vietnamese troops over the Paracel Islands in the South China Sea in 1974; marched against Vietnam in 1979; and came into conflict with a number of countries over the Spratly Islands since the mid-1980s. The PLA supported North-Vietnam during the Vietnam War, and deployed advisers and troops against American forces in Southeast Asia.

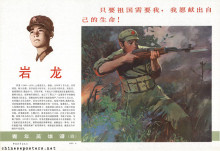

Charge the enemy till the last breath, 1970

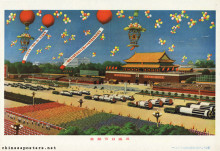

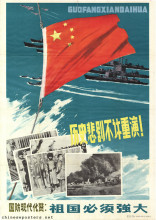

Over the past decades, the PLA has worked towards bringing Taiwan back into the fold. During the Taiwan Strait crisis of 1954-1955, and again in 1958, the Army bombarded the offshore islands of Quemoy (Jinmen) and Matzu (Mazu). In the 1980s, live ammunition was traded in for shells filled with propaganda materials, which the Taiwanese reciprocated in kind. In 1995-1996, the PLA was involved in naval and missile exercises off the coast of Taiwan in an attempt to influence the presidential elections then taking place in Taiwan. The peaceful resolution of the Taiwan issue has been high on the agenda of the successive generations of military and civilian PRC-leaders, including Hua Guofeng.

We must certainly complete the great task of unifying the mother country, 1978

Despite these activities, the PLA has always devoted its best energies to internal affairs. In the military sense, it pacified the country in the early 1950s, defeating Nationalist remnant troops and local militias. The Army occupied Hainan Island; participated in political campaigns to wipe out the landlord class and suppress counter-revolutionaries; and occupied Tibet. During the Great Leap Forward, the Army was used to prevent peasants from fleeing rural areas stricken by famine, and in the early 1960s, the military took over many government and State-functions.

Just after leaving the line of fire, still entering the battle field, 1974

Aside from its military and political functions, the PLA has been used as an economic resource as well. During the revolutionary war, wherever soldiers went, they participated in food production to supplement reserves in the area and lighten the burden on the local population. After the founding of the PRC, the PLA’s domestic economic role was enlarged. The huge number of demobilized soldiers, while retaining their military organization, was employed in civilian production, both in agriculture and in industry. The military moreover was involved in setting up state farms and massive land reclamation projects, in particular in the Northeast.

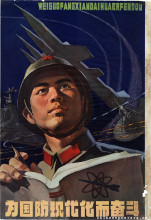

In the era of modernization, the role and position of the PLA in Chinese society has changed enormously. An Army career is no longer considered as one of the few available opportunities for social mobility: people rather try their luck as independent entrepreneurs. This has created problems for PLA-recruitment policies. On the other hand, the professionalization of the PLA-organization, now stressing arms over men, has made the Army rather reluctant to take in unskilled recruits from the countryside, preferring (urban) university graduates instead. Due to a reduction of the ranks (some 1.5-2 million in the last 15 years), a number of traditional PLA-functions has shifted to other organizations, in particular the People’s Armed Police (PAP). This latter organization has become the first line of defense against civil unrest. In that role, it has faced a lot of action in the ever more frequent conflicts with disgruntled peasants --protesting expulsion from their farmland to make way for industrial and/or urban development--; workers --opposing their dismissal--; and pensioners --clamoring against the paucity of their pensions. The PAP, backed when necessary by the PLA, has taken on much of the grass-roots work; over the years, it has become involved in combatting the regular floods that wreak increasing havoc in the countryside. PAP units were also deployed to ensure security for the 2008 Olympics in Beijing and other cities.

Martin Andrew, "Terrorism, Riots, and the Olympics: New Missions and Challenges for China’s Special Forces", China Brief  5:19 (13 September 2005)

5:19 (13 September 2005)

Flemming Christiansen & Shirin Rai, Chinese Politics and Society - An Introduction (London: Prentice Hall, 1996)

Alex Joske, Picking flowers, making honey -- The Chinese military’s collaboration with foreign universities (Barton: ASPI International Cyber Policy Centre, 2018)

Haiyan Lee, "The Charisma of Power and the Military Sublime in Tiananmen Square", The Journal of Asian Studies 70:2 (2011), 397–424

Li Danhui, "China-U.S. Détente and China’s Aid to Vietnam to Resist U.S. Intervention - The Vietnam Factor in China’s Foreign Policy Readjustment", Social Sciences in China 24:2 (2003), 165-176

Orna Naftali, "'Life is wonderful because of the military' -- People's Liberation Army recruitment campaigns in contemporary China", in Brendan Maartens & Thomas Bivins (eds), Propaganda and Public Relations in Military Recruitment -- Promoting Military Service in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries (Londond: Routledge, 2021), 178-191

Andrew J. Nathan & Robert S. Ross, The Great Wall and the Empty Fortress - China’s Search for Security (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997)

Kevin Pollpeter & Kenneth W. Allen (eds), PLA as Organization v2.0 (Montgomery: China Aerospace Studies Institute, 2018)

Qu Xing, "Chinese and Vietnamese Views on the Indo-China War: Strategic Unity and Tactical Differences", Social Sciences in China 24:2 (2003), 127-135

Richard C. Thornton, Odd Man Out - Truman, Stalin, Mao, and the Origins of the Korean War (Washington, DC: Brassey’s, 2000)

Zhang Baijia, "Cross the Yalu River - How China Handled a Crisis and Decided to Enter the Korean War", Social Sciences in China 24:2 (2003), 109-117

Xiaoming Zhang, "China’s 1979 War with Vietnam: A Reassessment", The China Quarterly 184 (2005), 851-874

![The Founding Ceremony of the Nation [PLA calendar 1985]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/images/e13-105_0.jpg?itok=WAZRw63q)