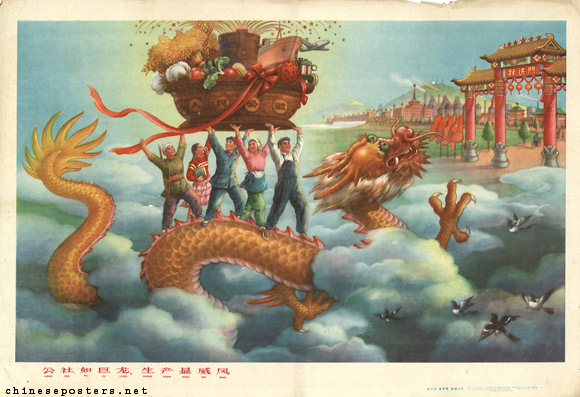

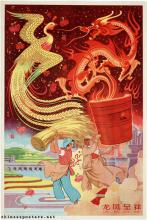

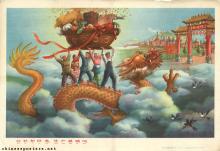

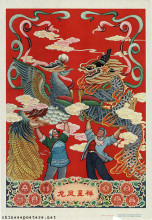

The commune is like a gigantic dragon, production is visibly awe-inspiring, 1959

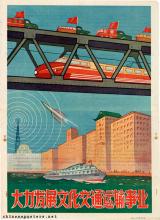

As a result of the successful economic reconstruction that had taken place in the early 1950s under the First Five-Year Plan, the Party leadership headed by Mao Zedong considered the conditions ripe for a Great Leap Forward (大跃进, Dayuejin) in early 1958. The Great Leap was not merely a bold economic project. It was also intended to show the Soviet Union that the Chinese approach to economic development was more vibrant, and ultimately would be more successful, than the Soviet model that had been followed studiously until then.

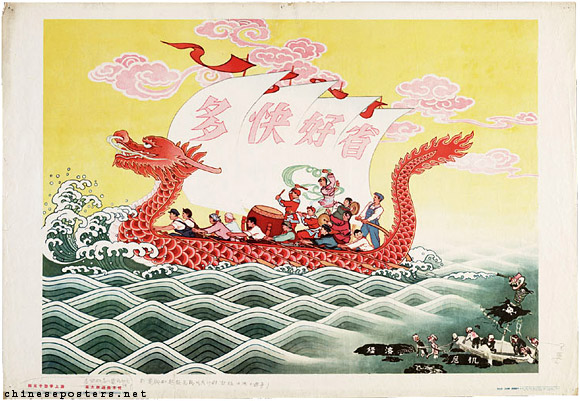

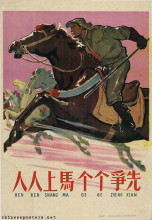

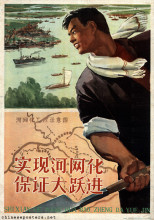

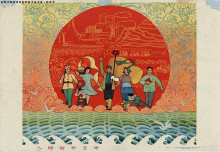

Braving the wind and the waves, each reveals their remarkable abilities, 1958

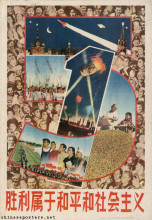

The Chinese people were to go all out in a concerted effort to surpass England in 15 (or even less) years and to make the transition from socialism to communism at the same time, thereby leaving the Soviet Union far behind. That, at least, was the plan, which brought to an abrupt stop the earlier, more cautious attempts to sustain the speed of China’s recovery and further development by Five-Year Plans. The more radical members of the leadership tried to outdo each other with more and more unrealistic calls for "greater, faster, better, [and] cheaper" production. The characters for this call are emblazoned on the sails of the ship in the poster below. The poster also tries to impress on the population how all this will improve their welfare, as opposed to that of the Taiwanese, who are shown in the right-hand corner as suffering under the GMD-regime and the presence of Americans.

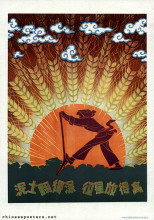

Go all out and aim high. The East leaps forward, the West is worried, 1958

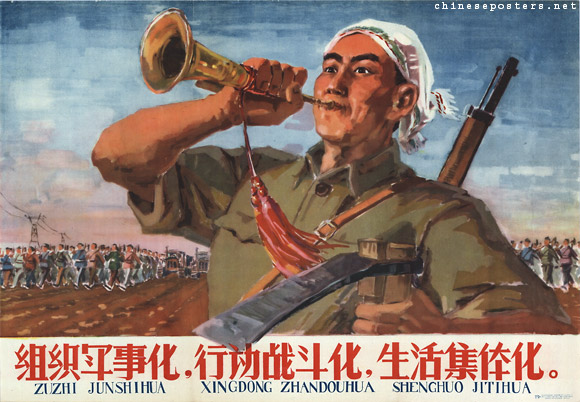

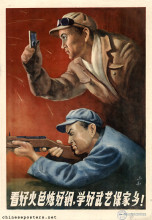

On the basis of an exaggerated belief in the power of ideology on human consciousness, the radicals were convinced that by putting "politcs in command", the objective difficulties created by lagging industrialisation and mechanisation could be overcome in a relatively short time. By relying on willpower, and by giving supremacy to the human, subjective dimensions of history, the people would be able to bring about a quick transformation of the concrete obstacles they encountered in the physical world. To mobilize this willpower, the Great Leap Forward, obviously, was accompanied by a concerted propaganda effort, the depth and breadth of which had hitherto not been seen.

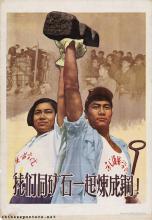

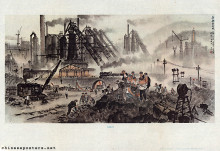

The Great Leap Forward took two forms: a mass steel campaign, and the formation of the people’s communes (人民公社, renmín gongshe). On the one hand, all the people in the country were organized to help produce the amount of steel that was needed to attain the goal of surpassing England. Life was militarized for this battle for steel.

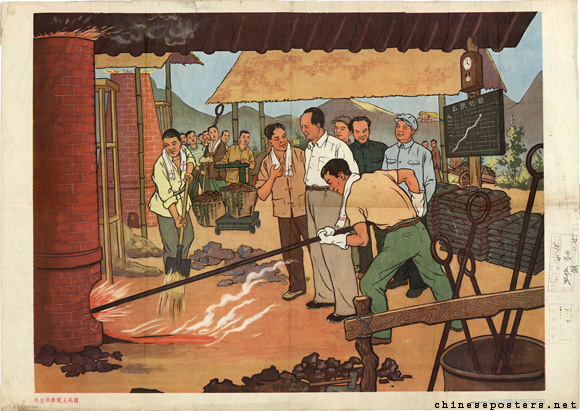

Chairman Mao visits a homemade blast furnace, 1958

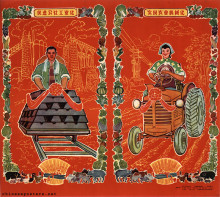

Everywhere, small backyard furnaces were built, where everybody pitched in in around-the-clock shifts. Quota for the collection of used iron had to be met, cooking pots were smashed, door handles were melted down in order to meet the production demands. Only later it became clear that the quality of this mass-produced people’s steel was so poor that no use could be found for it. The effects of this production battle proved to be disastrous for the environment. On the poster below, rows of such small backyard furnaces can be seen.

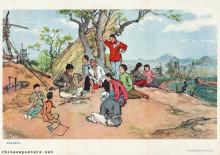

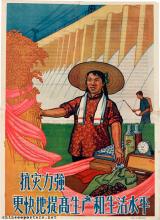

In the countryside, the various forms of rural cooperatives were merged into huge people’s communes. Rural life was completely collectivized, including mess halls where free food was supplied. Due to the excessive zeal of local officials, who were whipped up in the general atmosphere of enthusiasm while at the same time afraid to be branded as laggards, production figures that were unrealistic to begin with, were fixed higher and higher. Moreover, because everybody was involved in the battle to produce steel, labor power was lacking to bring in the harvests. If these amounts of food really could have been harvested, as the enthusiastic reports had promised, "communism was just around the corner", as the general belief in the autumn of 1958 seemed to be.

Strike the battle drum of the Great Leap Forward ever louder, 1959

By early 1959, it became clear that things were running out of hand. As a result of the massive production drives in steel and agriculture, both the production and transport sectors had become severely dislocated. The reality of the Great Leap Forward corresponded less and less with the picture painted in the reports to the leadership. Some leaders, including Chen Yun, started to express cautious warnings about the results of this "fever in the brain" which held China in its sway, while the more radical officials continued to proclaim imaginary victories in production.

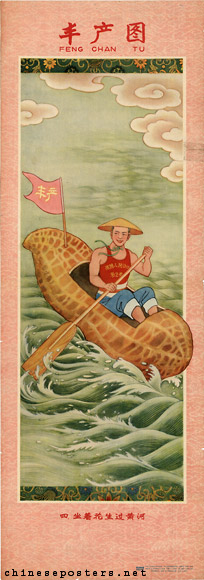

Crossing the Yellow River while sitting in a peanut, 1958

Dissatisfaction climaxed at the Lushan Plenum in July 1959. Originally, the meeting was intended to reign in the "leftism" of the movement, but it turned into a showdown between proponents of the movement (headed by Mao) and opponents (inadvertently headed by Minister of Defense Peng Dehuai). In a personal letter to Mao, Peng had criticized the extreme elements of the movement. Mao interpreted the letter as a personal attack and had it distributed for study and criticism by the other leaders present at Lushan. As a result of the Plenum, Peng was dismissed from his posts and replaced by Lin Biao. Instead of trying to find answers to the problems of the Great Leap, an anti-Rightist struggle was started.

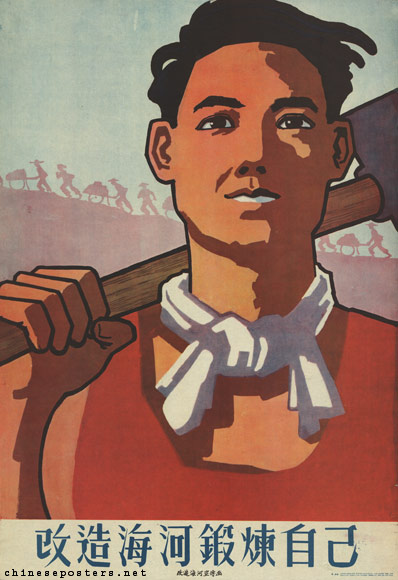

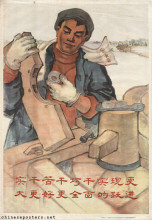

Transform the Hai River, temper yourself, 1958

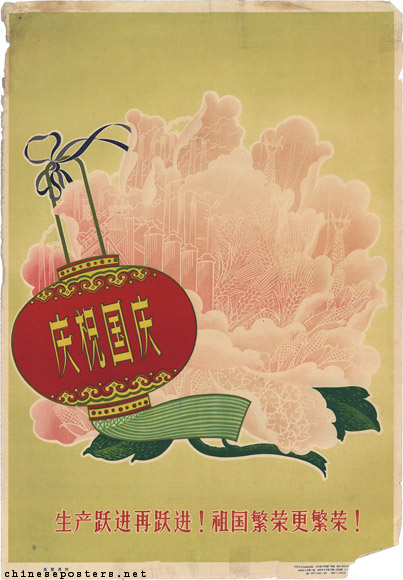

Despite the indications that the Great Leap had failed to reach its objectives, the movement continued to be upheld. During the celebrations of the Tenth Anniversary of the People’s Republic in October 1959, the "General Line of the Great Leap Forward, the people’s communes and the steel campaign" were reaffirmed. The movement turned into a disaster when in the period 1959-1961 China was struck by natural disasters. More than an estimated 30 to 40 million people died in the ensuing famine.

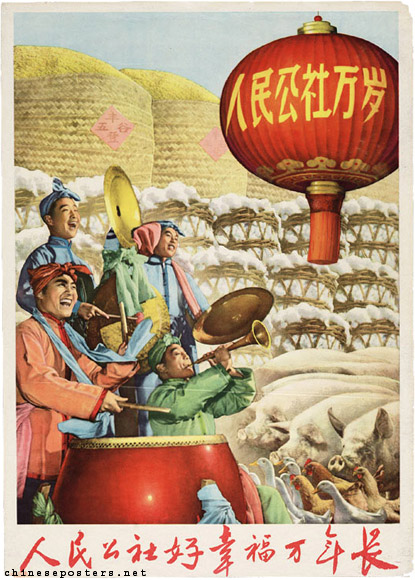

People’s communes are good, happiness will last for ten thousand years, ca. 1960

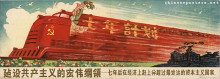

Long live the General Line! Long live the Great Leap Forward! Long live the People’s Communes!, 1964

Moreover, as a result of the break-up of the relations with the Soviet Union, China was confronted with total economic collapse. The readjustment of the economy started in 1961, and took place under the leadership of Liu Shaoqi, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun and others. During the Seven Thousand Cadres Conference (七千人大会) in Beijing in 1962, when Party officials gathered from late January to early February, and discussed the disastrous famines of the Great Leap Forward that began in 1958, Mao made a self-criticism and then took a step back from power, withdrawing to Shanghai. From there, he plotted his return to the pinnacle of power, which resulted in the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

Production takes leap after leap! The nation is becoming ever more prosperous!, 1958

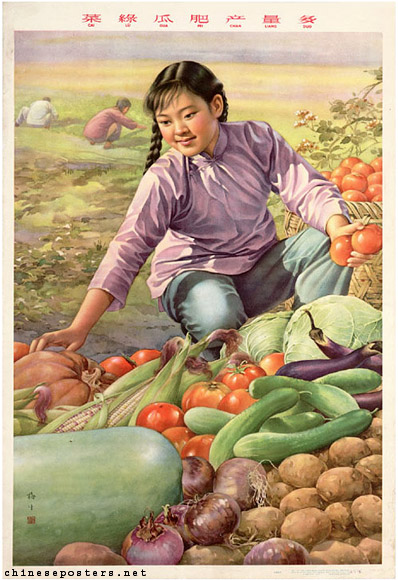

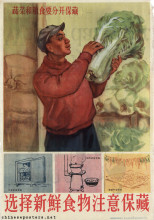

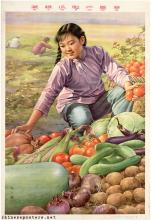

The vegetables are green, the cucumbers plumb, the yield is abundant, 1959

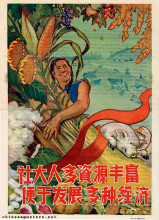

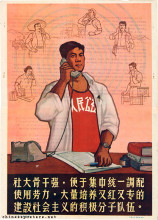

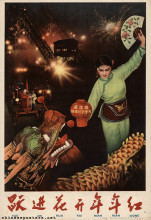

If the conditions in China turned from bad to worse from 1958 onwards, with the famine that resulted from the Great Leap as the nadir, how did the propaganda apparatus deal with this situation? It showed abundance.

The melons are sweet, grain and rice are fragrant, everybody tries the flavor, 1958

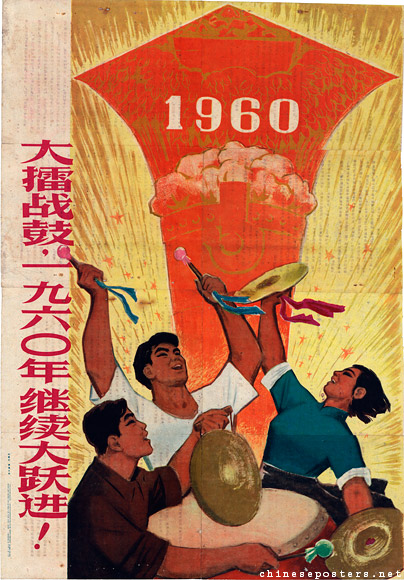

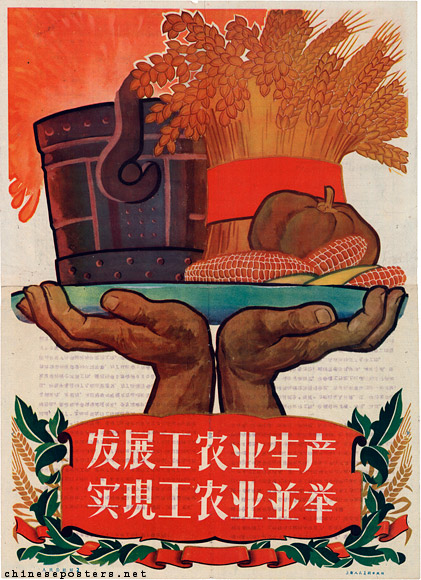

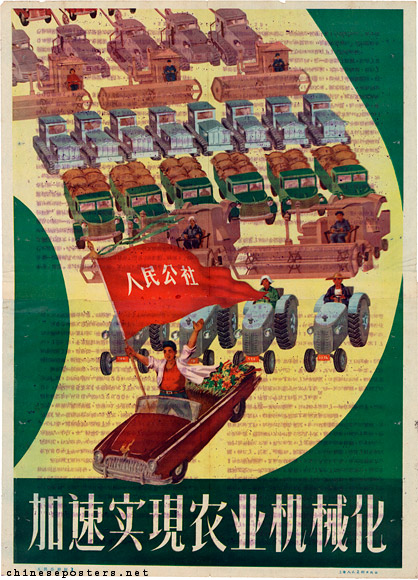

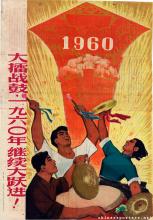

One of the essential aspects of propaganda is that it should reflect reality, while at the same time providing an optimistic outlook of what lies ahead. The posters below, all published in 1960, belied what actually had been taking place and continued to provide a surreal picture of life.

Beat the battledrum, in 1960 we will continue the Great Leap Forward!, 1960

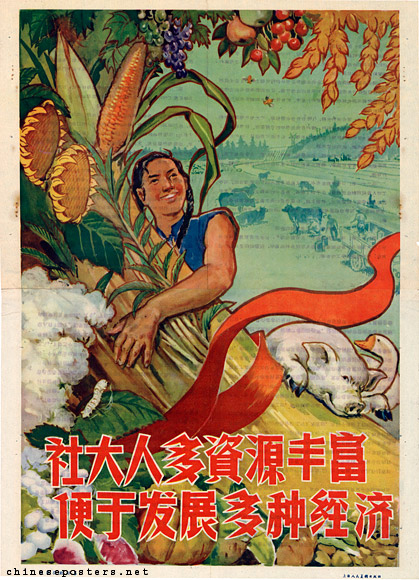

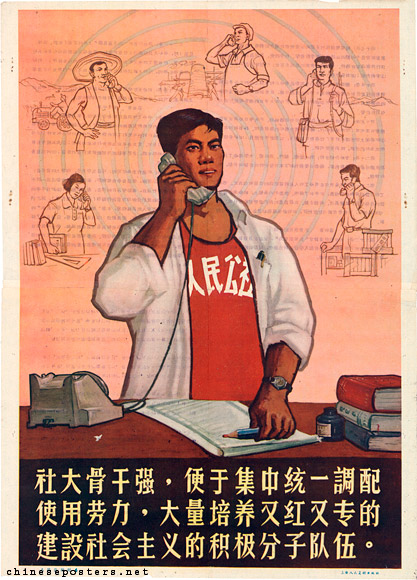

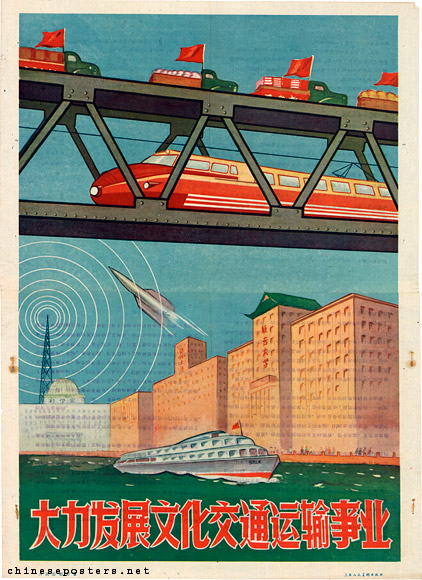

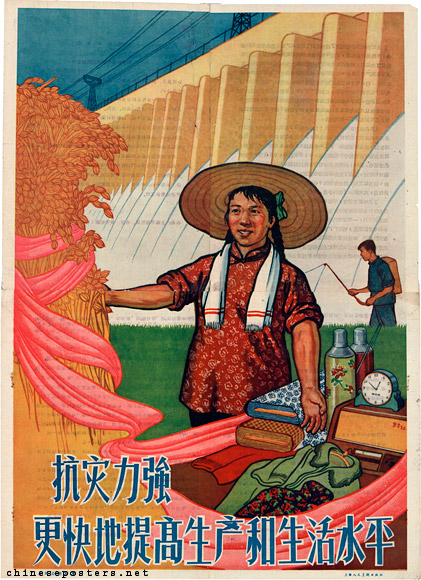

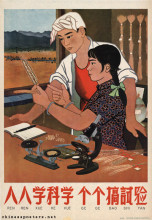

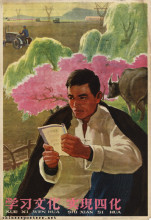

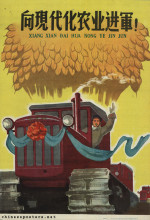

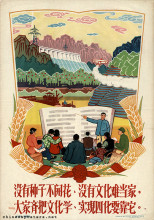

While the poster above, designed by none other than veteran artists Ha Qiongwen and Weng Yizhi, continued to drum up support for the already discredited developmental strategy, the anonymous images below -- parts of an incomplete series -- attempted to put a spin on what had been achieved. They all can serve as examples of the Illustrator-Realist style that marked the Great Leap.

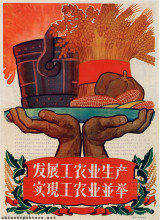

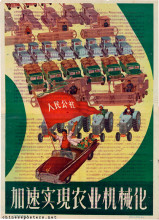

Speed up the mechanization of agriculture - People’s communes are good 3, 1960

The only indication of the material scarcity at the time is the fact that all these posters have either been printed on paper previously used to publish texts, or that they have been recycled for printing texts. Whatever the reason, the printed text shimmers through the very thin paper of mediocre quality.

Jasper Becker, Hungry Ghosts -- China’s Secret Famine (New York: Henry Holt, 1998)

Frank Dikötter, Mao’s Great Famine: The History of China’s Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958-62 (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2010)

Li Rui, Lushan huiyi shilu [True Record of the Lushan Plenum] (Peking: Chunqiu chubanshe/Hunan jiaoyu chubanshe, 1989) [in Chinese]

Li Zhisui, The Private Life of Chairman Mao -- The Memoirs of Mao’s Personal Physician (London: Random House, 1996)

Roderick MacFarquhar, The Origins of the Cultural Revolution, Volume II: The Great Leap Forward, 1958-1960 (Columbia University Press, 1987)

Roderick MacFarquhar, Timothy Cheek, Eugene Wu (eds), The Secret Speeches of Chairman Mao -- From the Hundred Flowers to the Great Leap Forward (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989)

Peter J. Seybolt, Throwing the Emperor from His Horse -- Portrait of a Village Leader in China, 1923-1995 (Boulder: Westview Press, 1996)

Frederick Teiwes and Warren Sun, China’s Road to Disaster -- Mao, Central Politicians, and Provincial Leaders in the Unfolding of the Great Leap Forward 1955-1959 (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 1998)

Felix Wemheuer, A Social History of Maoist China -- Conflict and Change, 1949–1976 (Cambridge University Press, 2019)

Yang Jisheng, Tombstone -- The Great Chinese Famine, 1958-1962 (Stacy Mosher & Guo Jian, trsl.) (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2008)