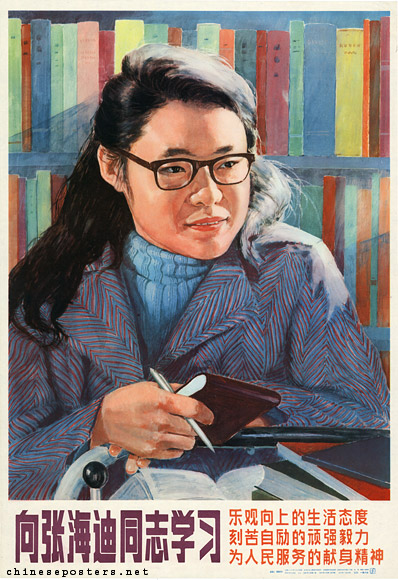

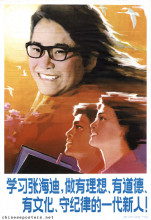

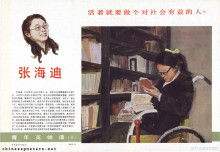

Learn from Comrade Zhang Haidi, 1983

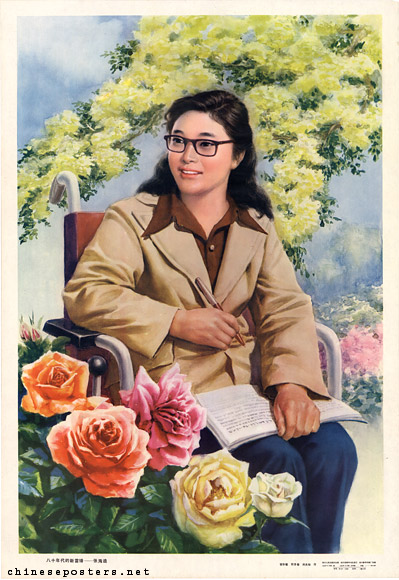

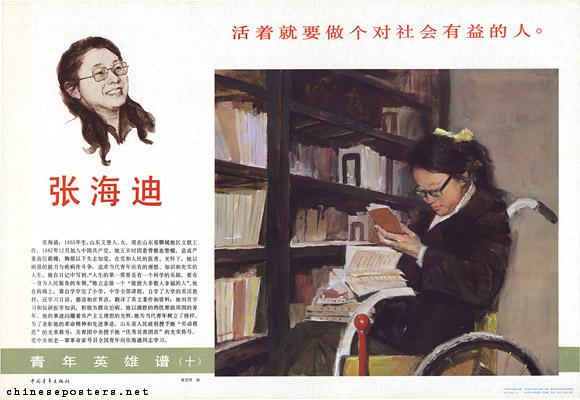

The model status of Zhang Haidi (张海迪, Jinan, Shandong Province, 1955), widely publicized in print and in propaganda posters from 1983 on, is an interesting one. Zhang Haidi, also known as Ling Ling, became a paraplegic at the age of five following four operations for the removal of tumors in her spine. When she received news that her illness was incurable, she was reported to have attempted to commit suicide by taking sleeping pills, an action usually considered as a betrayal of the revolution and as evidence of discontent with socialism and therefore as the act of a coward. She never went to school, but through diligent self-study, she learned to read books on politics, literature and medical science. She also learned foreign languages, including English, Japanese and German. She did not only function as a model because of her intellectual accomplishments or her devotion to serving others, but also because "... In Lei Feng, Chinese youths had to reach for communism. In Zhang Haidi, communism reaches for Chinese youths."

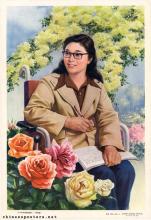

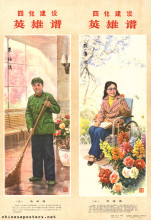

Her depicting that ‘a cripple’ could still function normally in Chinese society and even contribute to its modernization, was also clearly intended for all those who had been maimed and crippled during China’s ‘punitive expedition’ against its southern neighbor Vietnam in 1979. The attention suddenly given to invalids even might be linked to Deng Xiaoping’s son, Deng Pufang, who gained national prominence in the 1980s. Pufang ended up in a wheelchair as a result of a fall (or a push) from a sixth-floor window when he was subjected to Red Guard interrogations in August 1968, during the Cultural Revolution. As the Chairman of the Kanghua Foundation for the Disabled, he later was accused of shady business practices and embezzlement, and was forced to step down in the late 1980s. Zhang Haidi would succeed him as a chairperson of what is now called the China Disabled Persons' Federation  (CDPF) in 2008.

(CDPF) in 2008.

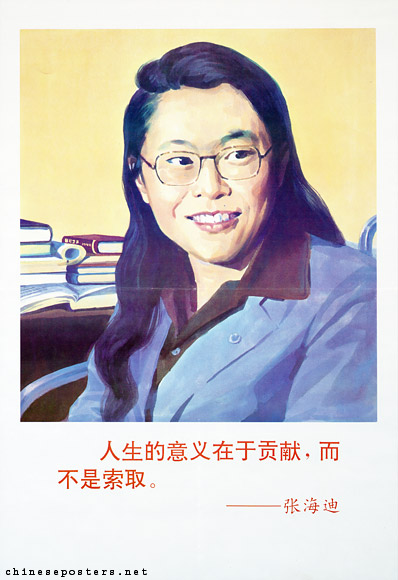

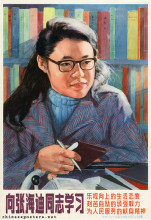

Zhang Haidi - A New Lei Feng of the 1980s, 1983

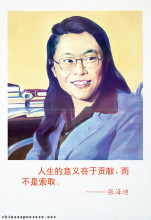

Persons like Zhang Haidi did not necessarily have to be martyrs for the revolutionary cause or pay with their lives in order to attain model status, although this did help. They simply were visualized in their ‘daily’ activities, which were clearly designed to make the population feel proud of being a woman, or a Chinese.

Over the years, Zhang Haidi’s shining example ceased to be held up, although she continued to play an advisory role in politics. As a member of consecutive sessions of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Consultative Conference (CPPCC), she remains an advocate for the rights of the disabled and for the improvement and accessiblity of public facilities for them. In 2001, Zhang, an avid internet surfer, was invited to act as the headmaster of China’s first online school. China Central Television (CCTV) devoted a program to Zhang during the marking of the May Fourth Movement in 2002. Aside from her duties as headmaster, Zhang has become a writer and translates foreign literature with her husband, Wang Zuoliang (王佐良).

Chiang Chen-ch’ang, "The New Lei Fengs of the 1980s", Issues and Studies, May 1984, pp. 22-42

He Pin and Gao Xin, CPC Princes (Toronto: Canada Mirror Books, 1992) [in Chinese]

Qian Jun, "A Model Woman’s New Focus: Internet and Environment", CRI Online News (originally published at http://web12.cri.com.cn/english/2001/Mar/11394.htm, link broken October 2009)

Shao Wu et al. (eds), 共和国群英谱 [Gongheguo qunyingpu - Register of heroes of the Republic] (Beijing: Zhongguo shaonian ertong chubanshe, 2003) [in Chinese]

Xiao Yu, "Zhang Haidi: Xiang shi yiyang shenghuo" [Zhang Haidi: A life like poetry], CCTV.com  , 1 May 2002 [in Chinese]

, 1 May 2002 [in Chinese]